Mapping the Tradecraft Behind the Investigation That Saved Ontario’s Greenbelt

By Levon William Enns-Kutcy, Josette Lafleur, Angeline Gisonni and Chris Arsenault

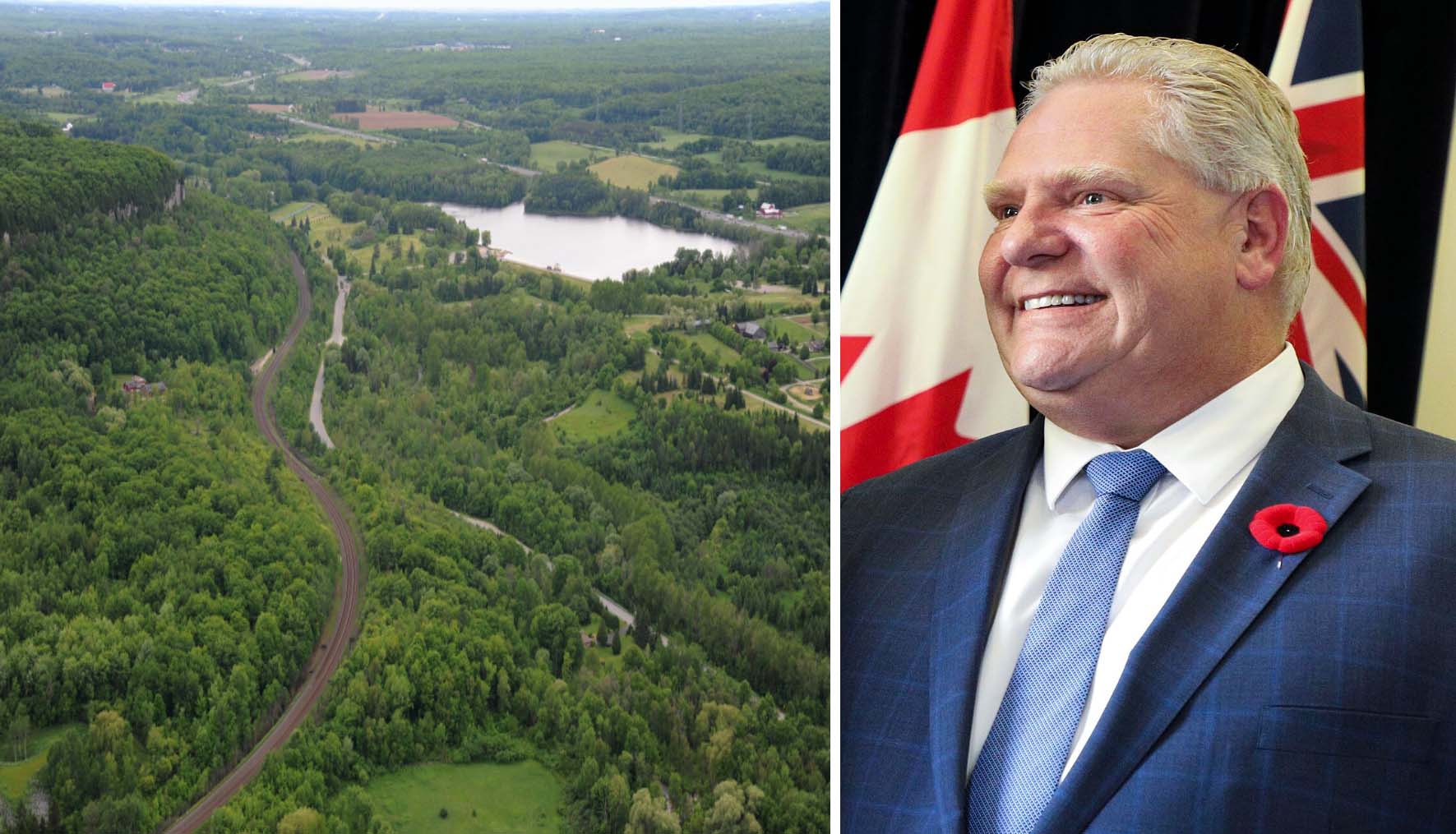

Journalists don’t always land the coup de grâce with their first report. Investigations often go the distance — round after round — piling up evidence until those in power can no longer sidestep the truth. That’s what happened when a team of reporters traced Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s Greenbelt carve-outs to developers, lobbyists, and donors poised to profit — and refused to let them off the hook.

When the government released maps showing which parcels it planned to remove following Ford’s bid to open Ontario’s Greenbelt, Narwhal reporter Emma McIntosh was skeptical. The carve-outs looked scattered, almost arbitrary. But her years covering environmental politics told her there was something more to it.

Knowing The Toronto Star had the resources to tackle a story of this scale, McIntosh informally pitched a joint investigation to friends at the paper. Reporters Noor Javed and Brendan Kennedy joined the effort and together the team assembled an incriminating paper trail. Working from interlinked, shared Google drive files, they traced each carve-out to land-title records and cross-referenced ownership with lobbying filings. The connections they uncovered were as clear as they were damning.

The investigation revealed a roadmap linking carve-outs to land already owned by developers who had long lobbied to free their properties from the Greenbelt — some even buying land just months before the deal was announced. Those findings triggered a cascade of follow-up exposés, spearheaded by the trio alongside journalist Charlie Pinkerton, that propelled the scandal squarely into the public eye and forced Ford to abandon his Greenbelt deal.

From piecing together maps, to open-source sleuthing through Ford’s daughter’s wedding photographs — and even a dogged series of phone calls to a Las Vegas hotel — the journalists join Chris Arsenault and Josette LaFleur to unpack the tradecraft that turned scattered parcels on a map into a scathing portrait of developers, lobbyists, and political insiders maneuvering behind the scenes to profit from protected land.

Josette Lafleur: How did this investigation develop, who flagged this story in the first place?

Emma McIntosh: I was at the Narwhal office late on a Friday when news broke that the Ford government was opening up parts of Ontario’s Greenbelt for development. After a couple of hours, I recognized one of the parcels: it belonged to a developer I had reported on before. I called David Bruser, the investigations editor at the Toronto Star, because the Star had resources the Narwhal didn’t. By the time we hung up, we’d agreed to “fire up the co-pro machine.”

Josette Lafleur: And what was the reasoning behind having the other journalists join in?

Emma McIntosh: Noor and I had done Greenbelt work together before, and Brendan, who is extremely organized and methodical, became our lead on land records. We knew we could do a better job as a team. Timing was critical — the government had posted the Greenbelt removals to the Environmental Registry of Ontario, triggering a 30-day consultation period. We had exactly 30 days to produce a story that could inform public debate.

Josette Lafleur: Can you walk us through that first investigation?

Noor Javed: The goal was to see if a pattern emerged. Eventually one did: many parcels had been purchased by recognized lobbyists within Ford’s tenure, in some cases right after his re-election.

Brendan Kennedy: That first investigation was about planting a flag. The government gave little explanation for why parcels were chosen. Our job was to raise questions: why these carve-outs, who stood to benefit, and what connections did those landowners have to Ford’s government?

Chris Arsenault: You had three main data streams — lobbying records, political donations, and land-title maps. How did you connect them?

Brendan Kennedy: The government’s maps of Greenbelt removals were deliberately vague, so we created our own system. We built a master spreadsheet in Google Drive, assigning each parcel a number. In each folder we cross-referenced the parcel with its land record: who owned it, when it was bought and sold, and for how much. Emma had a detailed political donations database from past reporting, which we paired with lobbying records to spot overlaps. That structure let us move quickly instead of losing time digging through old files.

Chris Arsenault: Students often find land registry searches intimidating, especially with vague government maps. How did you go from carve-outs to actual landowners?

Brendan Kennedy: Many of the government maps were rural parcels without addresses, just shaded blocks near roads or rivers. Using GeoWarehouse, our librarians had to visually match those shaded carveouts to parcel outlines in the database until shapes and landmarks lined up. Once we had matches, we pulled property records showing ownership and sales history, prioritizing the largest parcels. That revealed who stood to benefit.

Josette Lafleur: Regarding the second landmark story in this series, Charlie, how did you discover the donation at the Stag and Doe?

Charlie Pinkerton: The Stag and Doe was on August 11, 2022, a couple of months after Ford’s re-election. The next morning at a press conference, I heard a rumour about a “developer’s party” at the Premier’s house. When the Greenbelt changes were announced in November, that tip seemed a lot bigger. By mid-November I was filing Access to Information requests, starting with Ford’s calendar. On August 11 the calendar showed only a blacked-out block of time — a classic sign staff were covering up an undisclosed event.

A friend in the wedding industry suggested checking vendors, which led me to the photographer’s website. Clicking through, I found hundreds of photos from Kyla Ford’s wedding — including one of the seating charts showing developers and lobbyists who later benefited from the carveouts.

Josette Lafleur: Once you had that list, how did you approach contacting people?

Charlie Pinkerton: Many had government ties, but I reached out to everyone. Realtors, for example, were easy to contact and sometimes willing to talk. Even small confirmations like “yes, I was there” helped add credibility. It was about piecing together details from many phone calls.

Josette Lafleur: When it came to staff, how did you approach getting them to talk?

Charlie Pinkerton: In politics, people have different motivations: some have axes to grind, some see value in throwing others under the bus, and a few just want to do the right thing. That mix allowed us to make progress. There were also developers and landowners left out of the process, and their frustration became an entry point for sources.

Josette Lafleur: Tell me about how Mr. X got into your reporting.

Brendan Kennedy: When the Integrity Commissioner’s report landed, it mentioned “Mr. X,” who had been paid a million dollars to push land out of the Greenbelt. That raised immediate questions: Who was this, and why was his identity shielded?

The report offered clues: Mr. X was a former municipal politician with ties to development [working relationships with land developers and lobbying efforts tied to the housing industry]. For seasoned Star reporters, that pointed to John Mutton, the former mayor of Clarington. I leaned on my colleagues’ networks. We spoke to multiple sources — one lobbyist essentially confirmed it, another insider strongly hinted the same. Each layer built confidence.

The final step was accountability: confronting Mutton and giving him a chance to respond. He denied it, but the evidence outweighed his denial. That’s the threshold before publishing: enough credible evidence, from multiple directions, to responsibly put a name to “Mr. X.”

Chris Arsenault: You’ve done shoe-leather reporting: talking to sources, digging through records, filing access to information requests, even open-source sleuthing like wedding photos. Tactically, is there anything I’m missing?

Charlie Pinkerton: If you want to go down the Vegas rabbit hole, there was a non-traditional approach there.

Chris Arsenault: A Vegas rabbit hole definitely piques my interest.

Charlie Pinkerton: In summer 2023, before the Auditor General and Integrity Commissioner weighed in, I chased a tip about a Las Vegas trip. Back in 2020, the Premier’s second-in-command, a future housing policy director, and a cabinet minister traveled there with a developer whose land was later freed from the Greenbelt.

Confirming that took months. The breakthrough came by repeatedly calling the Wynn Hotel — front desk, spa, golf course, restaurants. I never lied or misrepresented myself; I just asked. Staff eventually confirmed bookings, including a “good luck ritual” massage on a key date. CTV later reported that three officials received it together.

The Integrity Commissioner’s account later conflicted with what we knew, but our reporting stood. Weeks later, Ford apologized and pledged to reverse the Greenbelt changes.

Persistence matters — sometimes investigative reporting is just picking up the phone until someone talks.